- 30.01.2026

In March 2006, Ukraine ratified[1] the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC), thereby joining the key international instrument designed to protect populations from the harmful effects of tobacco and nicotine.

Since then, Ukraine has introduced a number of effective tobacco control measures that have delivered tangible results: smoke-free workplaces and public indoor spaces, bans on tobacco advertising and sponsorship, the introduction of health warnings, and increases in excise taxes. Between 2005 and 2017, smoking prevalence among children decreased by 43%, and among adults it declined by 20% between 2010 and 2017[2].

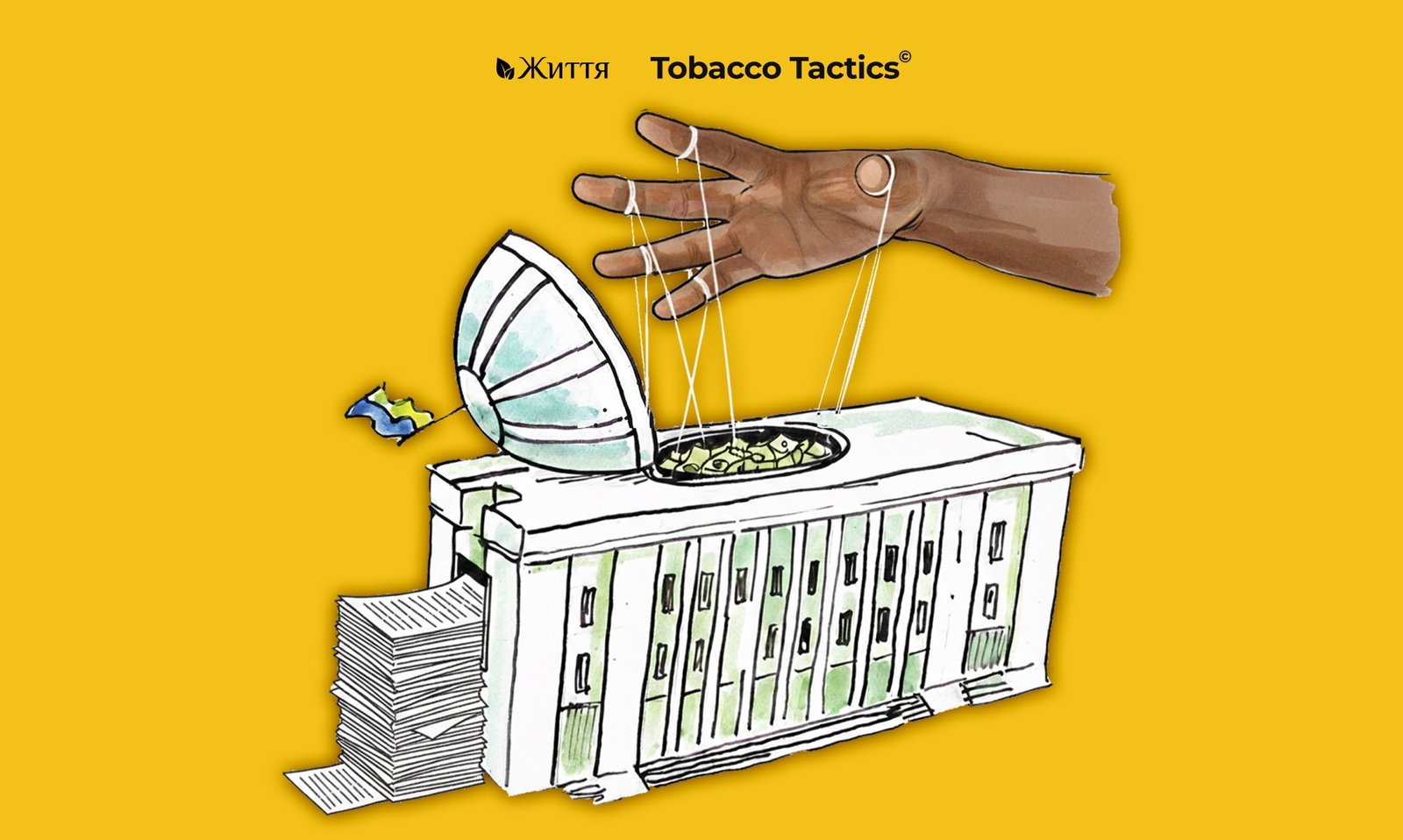

At the same time, any legislative initiative aimed at protecting public health inevitably faces resistance from the tobacco industry, whose objective is to sell tobacco and nicotine products and preserve influence over policy-making processes in order to continue recruiting new consumers – primarily among children[3].

The Guidelines for implementation of Article 5.3 of the WHO FCTC state:“The tobacco industry should not be a partner in any initiative linked to setting or implementing public health policies, given that its interests are in direct conflict with the goals of public health.”[4]

The corporate political activity of tobacco companies is described in detail in the “Policy Dystopia Model,”[5] developed on the basis of a large body of evidence, including internal industry documents.

According to this model, when confronted with tobacco control initiatives designed to protect the population, the industry seeks to achieve one of several desired outcomes:

The WHO identifies the following regulatory tactics used by the tobacco industry:

Tobacco industry lobbying tactics include:

One of the key legal tools used by the tobacco industry is the registration of alternative bills that serve the commercial interests of the industry, as well as the mass submission of amendments (so-called “regulatory spamming”) aimed at delaying consideration, weakening decisions, postponing entry into force, distorting legislation, and making enforcement impossible.

Below, we examine how this tactic is applied in Ukraine using two laws as examples: Law No. 1978-IX[7] (strengthening non-price measures) and Law No. 4115-IX[8] (excise tax policy).

Law of Ukraine No. 1978-IX “On Amendments to Certain Laws of Ukraine to Protect Public Health from the Harmful Effects of Tobacco” (originally Draft Law No. 4358) was adopted in December 2021 and introduced significant strengthening of non-price tobacco control measures, including:

However, due to interference by the tobacco industry, the draft law ultimately excluded provisions on banning tobacco displays at points of sale (a form of tobacco advertising), introducing combined (text + image) health warnings covering 65% of the pack for HTPs, and banning flavoring additives for HTPs.

So-called “legislative spamming” refers to the registration of multiple alternative bills to the main draft law with the aim of weakening, delaying, or blocking effective regulatory solutions.

In this way, the tobacco industry – through affiliated members of parliament – seeks to exploit legislative procedures to protect its commercial interests.

During the consideration of Law No. 1978-IX, five alternative initiatives were registered to block and weaken it. All were substantially weaker than the main draft and sought to exclude HTPs and tobacco-heating devices from full regulation. They would have allowed flavored HTPs, permitted their use in indoor public spaces, introduced smaller health warnings than those proposed in the main draft, omitted bans on advertising HTPs and heating devices, and weakened the legislation in force at that time. These alternative initiatives contradicted Ukraine’s international obligations to implement the WHO FCTC and Directive 2014/40/EU.

In several cases, the same MPs registered multiple alternatives—a typical sign of legislative spamming. Marian Zablotskyi and Yevhen Petruniak registered Draft Laws No. 4358-1[9] and No. 4358-5[10], which among other things proposed allowing smoking in restaurants again. Ivan Shynkarenko registered Draft Laws No. 4358-2[11] and No. 4358-4[12].

Moreover, some initiators of the alternative draft laws had previously been exposed as defending the tobacco industry’s interests. Among them:

Another tobacco industry tactic is the submission of a large number of amendments in order to delay and complicate the legislative process. This is one of the most common and least transparent methods of influence:

Before the second reading of Draft Law No. 4358, 515 amendments were submitted, of which 425 (83%) were rejected and only 90 were accepted[20].

For example, Vadym Halaichuk, the initiator of the alternative Draft Law No. 4358-5, submitted 56 amendments – 45 of which clearly weakened either the main draft’s tobacco control provisions or existing tobacco control norms. Some of these amendments proposed removing key definitions from the law, such as “premises” and “devices for consuming tobacco products without combustion” (represented in Ukraine by brands such as glo and IQOS). The absence of clear definitions would have created loopholes for manufacturers, importers, and unscrupulous hospitality businesses.

Member of Parliament Andrii Puziichuk submitted 178 amendments, a significant portion of which were limited to formal edits of individual words or wording and did not change the substance of the draft law, and instead artificially overloaded the process to delay its consideration. Some amendments were overtly harmful. In particular, Amendment No. 45 proposed introducing the following definition of hookah tobacco: “a tobacco product for smoking that may be consumed through a hookah. If such tobacco can be used both for a hookah and for roll-your-own cigarettes, it shall be considered roll-your-own tobacco.” Such a provision would have significantly weakened the regulation of hookah tobacco.

MP Marian Zablotskyi, through amendment No. 316, proposed allowing the use of smokeless tobacco products in hospitality venues again: “The use of smokeless tobacco products is prohibited: […] in the premises of hospitality establishments, except in specially designated areas (at the discretion of the establishment).”

Thus, the case of Law No. 1978-IX demonstrates that the mass submission of amendments is a deliberate tobacco industry tactic aimed not at improving legislation, but at delaying the process and weakening public health regulation. Even partially adopted amendments can create regulatory gaps that may later be exploited by the tobacco industry to circumvent the law. This poses a serious risk to the effectiveness of tobacco control policy and requires special attention from lawmakers, civil society, and experts.

The situation with Law No. 4115-IX “On Amendments to the Tax Code of Ukraine and Other Laws of Ukraine on Revising Excise Tax Rates on Tobacco Products” (originally Draft Law No. 11090) was somewhat different, as the initiative was developed by the Ministry of Finance of Ukraine with direct interference from the tobacco industry from the outset (as openly stated by the Deputy Minister of Finance of Ukraine[21]). At the same time, even in such cases, the industry continues to interfere during the revision and adoption stages, seeking not only to preserve existing concessions but also – where possible – to secure additional regulatory preferences.

Positive decisions | Weak decisions |

Conversion of excise duty calculations on tobacco and nicotine products into euros to avoid the impact of devaluation. | Plan to increase excise duties on cigarettes to €90 per 1,000 cigarettes by 2028 (the minimum level in the European Union, as required by Directive 2011/64/EU[22]). |

Setting the rate for e-cigarette liquids at €300 per liter in 2025. | Creation of a 25% excise tax preference for HTPs compared to cigarettes (€72/1,000 items by 2028). |

Despite numerous statements and indisputable arguments from the public, the Ukrainian government and parliament, under pressure from the tobacco industry, abandoned the effective practice of harmonized taxation of cigarettes and HTPs in favor of tobacco companies, two of which are international sponsors of the war[23], and introduced a weak plan to increase excise taxes on tobacco products, which will result in increased consumption of tobacco products, significant shortfalls in Ukraine’s war budget, and a widening gap with the level of taxation in the EU (divergence).

Four alternative draft laws were submitted to Draft Law No. 11090. Two of them (No. 11090-1[24] by Yevhen Petruniak and Andrii Nikolaienko, and No. 11090-2[25] by Ihor Kryvosheiev), like the main bill, proposed a weak and extended timeline to reach the EU minimum excise level and introduced a 25% tax preference for HTPs compared to conventional cigarettes. As such, these initiatives did not create genuine competition between policy approaches, but rather created an illusion of broad support for the so-called “compromise” solution.

Once again, the MPs initiating the alternative draft laws had repeatedly been exposed as defending tobacco company interests:

A total of 442 amendments were submitted to Draft Law No. 11090, of which 412 were rejected (93%)[29]. This scale of amendments indicates not constructive revision, but systematic amendment pressure aimed at complicating and diluting the legislative process.

During the review of this draft law, the same MPs registered series of amendments to the same product categories, not offering alternative excise policy models but presenting almost identical schedules for rate increases with minor formal differences (amendments No. 343, 344, 346 by I. Kryvosheiev; No. 350, 352, 353 by a group of MPs (D. Razumkov, V. Bozhyk, Y. Petruniak, R. Babii, I. Yunakov, O. Dmytriieva, L. Shpak, V. Kozak)). These variations lacked any independent political or economic justification and artificially complicated the legislative process.

MPs Andrii Kit and Robert Horvat proposed shifting cigarillo taxation from a per-stick basis to a weight-based (per kilogram) approach, which significantly changes the fiscal logic and creates additional risks for administration and potential loopholes (amendments No. 26, 62, 328).

A group of MPs (D. Razumkov, V. Bozhyk, Y. Petruniak, R. Babii, I. Yunakov, O. Dmytriieva, L. Shpak, V. Kozak) attempted to cancel the transition to euro-based taxation and keep excise duties in hryvnia equivalents (amendment No. 78). As Ukraine’s experience has shown, hryvnia-based taxation devalues the real level of excise duty over time and undermines both fiscal objectives and public health goals. In addition, keeping excise taxation in hryvnia distances Ukraine from harmonisation with the EU, where excise duties are set in euros, complicates predictability for the state, and reduces the effectiveness of excise taxes as a tool to reduce tobacco consumption.

Overall, the above-mentioned group of MPs registered 46 amendments, 100% of which were rejected.

The avalanche of amendments to Draft Law No. 11090 also bore the signs of spamming, as the same MPs registered dozens of formal amendments or attempted to further weaken even the “compromise” draft law developed with tobacco industry influence.

Systematic tobacco industry interference in the legislative process weakens the institutional capacity of parliament, undermines the effectiveness of state tobacco control policy, and reduces public trust in MPs. As a result, the state fails to provide adequate protection for citizens from the tobacco and nicotine epidemic, which leads to significant human and economic losses: every year in Ukraine around 100,000 people die prematurely[30], estimated economic losses amount to 3.2% of GDP[31], and more than 325,000 people[32] live with a substantial deterioration in quality of life due to diseases related to tobacco use.

In order to sustain profits, the tobacco industry must constantly replace deceased consumers with new ones. One of its strategies is the creation and aggressive promotion of new tobacco and nicotine products, the health impact and regulation of which often take years to establish. For example, the prolonged lack of proper regulation of electronic cigarettes in Ukraine has resulted in one in five children (20%) aged 13–15 using e-cigarettes, 7% using HTPs[33]. The preferential treatment for HTPs (including flavorings and the absence of combined health warnings) undermines achievements in protecting the population from tobacco and systematically weakens public health policy[34].

Given this, Ukraine needs more decisive and systemic measures to protect health policy from tobacco industry interference, including through compliance with Article 5.3 of the WHO FCTC and its Guidelines, transparency in the legislative process, and preventing tobacco industry involvement in shaping policies aimed at protecting the population from the harms of tobacco and nicotine.

[1] https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/897_001#Text

[2] https://moz.gov.ua/uk/poshirenist-kurinnja-v-ukraini-zmenshilas-na-20#

[3] https://center-life.org/novyny/back-to-school-iak-tiutiunova-industriia-poliuie-na-shkoliariv-v-interneti/

[4] https://fctc.who.int/resources/publications/m/item/guidelines-for-implementation-of-article-5.3

[5] https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.1002125&utm_source=chatgpt.com

[6] https://applications.emro.who.int/docs/FS-TFI-199-2019-EN.pdf

[7] https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/1978-20/ed20231123#Text

[8] https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/4115-20#Text

[9] https://itd.rada.gov.ua/billinfo/Bills/Card/4780

[10] https://itd.rada.gov.ua/billinfo/Bills/Card/25771

[11] https://itd.rada.gov.ua/billinfo/Bills/Card/4819

[12] https://itd.rada.gov.ua/billinfo/Bills/Card/25780

[13] https://youcontrol.com.ua/catalog/company_details/40142048/

[14] https://www.pmi.com/resources/docs/default-source/our_company/transparency/charitable-contributions-2017.pdf

[15] https://www.pmi.com/resources/docs/default-source/our_company/transparency/charitable-2018.pdf?sfvrsn=d97d91b5_2

[16] https://www.pmi.com/resources/docs/default-source/our_company/transparency/social-contributions-2019.pdf

[17] https://w1.c1.rada.gov.ua/pls/zweb2/webproc4_1?pf3511=70110

[18] https://drive.google.com/file/d/1VzwM_9_3bvesSkPFcqaGMAjtBw5HoAIu/view?usp=sharing

[19] https://opendatabot.ua/c/03081460

[20] https://w1.c1.rada.gov.ua/pls/zweb2/webproc4_1?pf3511=70397#alt_tab

[21] https://drive.google.com/file/d/1dXUTOiS16gDIlbrxEmt9ToOSHIO9qfw_/view

[22] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32011L0064

[23] https://nazk.gov.ua/en/news/nacp-adds-philip-morris-international-and-japan-tobacco-international-to-the-list-of-international-war-sponsors

[24] https://itd.rada.gov.ua/billInfo/Bills/Card/43920

[25] https://itd.rada.gov.ua/billInfo/Bills/Card/43930

[26] https://itd.rada.gov.ua/billinfo/Bills/Card/45085

[27] http://komzdrav.rada.gov.ua/uploads/documents/32399.pdf

[28] https://drive.google.com/file/d/1o8w4Bit57B8Fpwt_MfMmlioN9G7K5t9p/view

[29] https://itd.rada.gov.ua/billinfo/Bills/pubFile/2646332

[30] https://moz.gov.ua/article/news/igor-kuzin-medichni-poperedzhennja-pro-shkodu-kurinnja-zajmatimut-65-ploschi-pachki—ce-posilit-efekt-antitjutjunovih-obmezhen

[31] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5801657/

[32] https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/

[33] https://center-life.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/gyts2023_ukraine_uk.pdf

[34] https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/8372fe0f-2bf7-4272-bb42-9e1428db9ac4/content